By Julie Musick Hillgrove (Copyright 2021. Used with permission of the Author)

A slightly different version can be found in the YHA Newsletter March/April 2021.

Following the Revolutionary War, pressure on Native Americans in the east to move west increased. Before the Revolutionary War, the British attempted to hold back the swell of people in the east from entering and settling on the territories of the Native Americans west of the Appalachian Mountains. Their efforts were unsuccessful. The British restriction from settling west contributed to the causes of the Revolutionary War.

There were many treaties written and broken that brought more Native Americans to today’s Delaware County. Many came after the Revolutionary War and the Treaty of Greenville in 1814.

Two-hundred-years ago, Delaware County began recording the first permanent white settlements on public land but first, that land had to be available to purchase. In 1818, the Treaty of St. Mary’s was signed as six individual treaties with many Native American tribes. The treaties resulted in the purchase of 8,500,000 acres of Native American land within central Indiana by the federal government. The land is often referred to as the “New Purchase” or “public land” in land abstracts and descriptions.

When I grew up in Yorktown, Indiana, my playground was the woods along the White River. I had great curiosity about the Native Americans in the area. Who were they? Where did they go? This was Miami territory, although the Miami lived mostly to the north with settlements along the Mississinewa River in today’s Delaware County. The Delaware tribe, forced from the east, were late comers in the area arriving along the White River about 1790-95. The Delaware settled here with permission of the Miami who considered central Indiana, southwest Michigan and western Ohio their territory. But still more tribes arrived.

Of the tribes signing treaties in 1818, the Delaware (Lenape) reserved the right to occupy their lands along the White River for an additional three years, giving them until 1821 to leave. The tribe moved earlier than the deadline so, by 1820, most Native Americans in present-day Delaware County had moved west of the Mississippi River or to reserves in the north. Watch a film about the Lenape and their history.

A few special land reserves were set aside in the treaties for individual Native Americans. One included 320 acres for Samuel Cassman (Casman)at the confluence of the White River and Buck Creek.

Cassman’s is the earliest recorded land registered in Delaware County on 16 Sep 1820. It was a prime location in the north half of section 22 in what is now the town of Yorktown, Indiana.

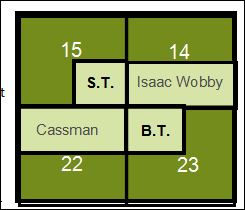

Besides Cassman, there were three other Native American reserves in Mt. Pleasant Township adjoining Cassman’s land: Solomon Tindell, received the southeast quarter of section 15, (160 acres) to the north of Cassman in 1824; Benomi Tindell, received the northwest quarter of section 23, (160 acres), east of Cassman in 1824; and Isaac Wobby, received the south half of section 14, (320 acres).

Wobby claimed to have cleared and planted 10-acres of the land in an 1818 letter but he was tenaciously following the Delaware Indian Agent, John Johnston, to Ft. Wayne and then Piqua, Ohio in 1818. Isaac Wobbly died soon after the treaty was signed. There was a court battle over whether his widow, Jane, could inherit and sale his land. His land reserve wasn’t registered in Delaware County until 1832 and was in litigation for many years thereafter. Ultimately, Goldsmith Gilbert purchased all of the Indian Reserves in Delaware County. He sold Cassman’s reserve to Oliver H. Smith who platted the town of “York Town” in 1837, naming the town after the Indians who migrated to central Indiana from New York.

The 1818 treaty wrongly identifies these individuals as Delaware Indians in full or part. In truth, all but Cassman were Brothertown (Brotherton) Indians.

The New Purchase land needed to be surveyed and could not be legally sold, although that fact deterred few. In May of 1822, the Ft. Wayne land office was created. According to Kemper in A Twentieth Century History of Delaware County Indiana (1908), the land in Delaware County was sold through the Ft. Wayne land office with few exceptions. Many people flooding into the central part of the state were squatters.

Who were the Native Americans with land reserves in Mt. Pleasant Township?

While Cassman was said to be half-Delaware, (Cassman’s son refers to his father as a “York” Indian in a letter), it is still unknown why he received such a generous grant. The others, the Tindells, father and son, and Wobby, were part of the Brothertown (Brotherton) Indian Nation (Moravian or Christian Munsee)—a Christian tribe formed in 1785 from many related tribes including some Delaware (Lenape), Pequot, Stockbridge-Munsee, Mohican and Oneida.

The Delaware and Miami gave permission to all related remnant tribes and bands in the east to live along the west fork of the White River prior to the treaty but things didn’t quite work out for those they invited.

In 1818, while cementing the final details of their move to live along the White River as discussed in 1809, a delegation from the Brothertown tribes arrived from New York and Massachusetts to Indiana. The Brothertown delegation stopped at villages along the White River, including Chief William Anderson (Kikthawenund). Learning of the treaty, the group hurried to Ft. Wayne to find Elder Isaac Wobby and his wife, Jane. Wobby had already gone to observe the negotiations of the Treaty of St. Mary’s, Ohio, not letting the Delaware Indian Agent, Johnston, go too far without his presence.

The Brothertown delegation arrived the day prior to the treaty’s conclusion. The Miami and Delaware affirmed the agreement that they had with the Brothertown when they signed the treaty. Fortunately for the some of the Brothertown, those rights were acknowledged in part. Isaac Wobby’s attendance and tenacity helped ensure the individual land reserves. The reserves were most likely given to sell to finance their move west of the Mississippi and not for them to settle upon. The Stockbridge-Munsee sent no one to St. Mary’s and received nothing as a result.

None of those receiving a reserve lived on the land except for Cassman and, possibly, Wobby, for a short time. In correspondence, Wobby claimed to have cleared 10-acres on his reserve but wasn’t living on the land at the time of the treaty. There were also reserves for Elizabeth Pet-cha-ka and Jacob Dicks, both Brothertown Indians, but these reserves were not in Mt. Pleasant Township.

Rebekah Hackley received a full section of land, plus additional land to compensate for the White River running through her property, 672 acres in all, at “Munsee Town”. The land was “for her inheritance”. The land became known as the Hackley Reserve and encompasses today’s Muncie, Indiana. She was living in Fort Wayne at the time of the treaty.

Although Rebekah Hackley was a granddaughter of Miami Chief Little Turtle (who had numerous grandchildren), her own father, William Wells, had served with the U.S. military after the Revolutionary War. Wells was killed in the 1812 Massacre of Ft. Dearborn (at Chicago). Wells Street, in downtown Chicago, is named for him. Rebekah’s husband, Capt. John “James” Hackley, Jr., negotiated the treaty between the Native Americans and Hackley’s boss, General Anthony Wayne. Hackley was a long-time member of the U.S. military and earlier militias. He likely ensured that he and his wife were treated generously.

Also of note, the Congressional Record of 1820 records a petition from William Conner (THE “Conner” of Conner Prairie Farm) for consideration of a pre-exemption of land in the “Delaware Towns” where he had been living among the Delaware. Conner had married a Delaware woman, Mekinges, daughter of Chief Anderson, and wanted to remain with his wife and rear his six children on lands that he had improved. The petition was tabled for a time.

Unfortunately for Conner, the Delaware Indians had to move. The Delaware had a matriarchal linage and Mekinges wanted to move with the tribe west. When the Delaware left Indiana in 1820, Conner rode with his wife and children for a day. He turned around while she continued with the children to Kansas via Missouri, later moving to Indian Territory in Oklahoma with her tribe. Conner chose to stay in Indiana. He remarried. The six Conner children who were half-Delaware were denied rights to Conner’s estate after Conner’s death.

Under pressure from the United States government in the 1830’s, the remaining Brothertown (Brotherton) in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New York, together with the Stockbridge-Munsee, Moheakunucks (Mohican), and some Oneida, moved to Wisconsin, taking ships through the Great Lakes. They remain settled in Wisconsin. Other tribe members went to Ontario, Canada while others, as we see from above, had already settled in Indiana as early as 1790 had moved to Indian Territory via Missouri and Kansas. Some of the Indiana group when to Wisconsin or Canada but most ended their journey in Oklahoma.