Two-hundred-years ago, Delaware County began recording the first permanent white settlements on public land. In 1818, the Treaty of St. Mary’s was signed as six individual treaties with many Native American tribes. The treaties resulted in the purchase of 8,500,000 acres of Native American land within central Indiana by the federal government. The land is often referred to as the “New Purchase” or “public land”.

When I grew up in Yorktown, my playground was the woods along the White River. I had great curiosity about the Native Americans in our area. Who were they? Where did they go? This was Miami territory, although the Miami lived mostly in the north of present-day Indiana. The Delaware tribe, forced from the east, were latecomers to the area, arriving about 1790. The Delaware were here with permission of the Miami.

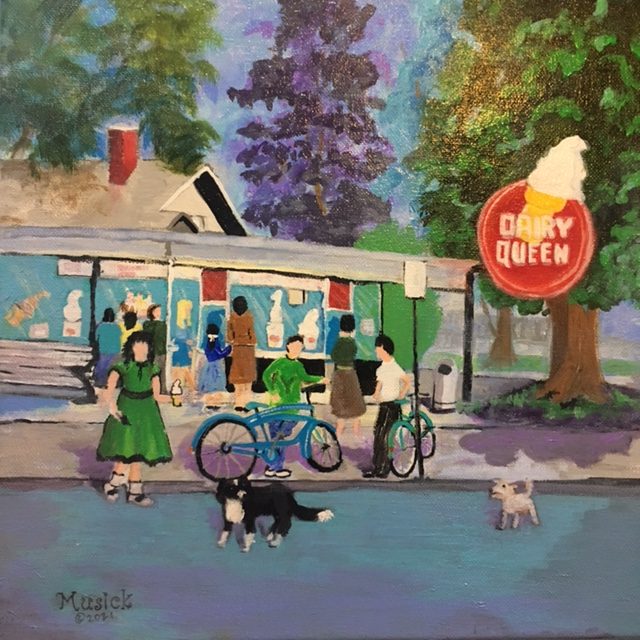

My brothers, Brad and Chris Musick, often found arrowheads in the woods and field behind our Pleasant Hills subdivision and validated the existence of REAL Indians HERE. I sat often in a special, majestic Sycamore tree branching over the White River, reading and reflecting. It was peaceful and I felt close to the land. I wondered how many had sat in that tree in reflection before me.

Of the tribes signing treaties in 1818, the Delaware (Lenape) reserved the right to occupy their lands on the White River for an additional three years, giving them until 1821 to leave. The tribe moved earlier than the deadline so, by 1820, most Native Americans in present-day Delaware County had moved west of the Mississippi River or to reserves in the north. Watch a film about the Lenape. http://delawaretribe.org/blog/2014/05/24/the-lenape-on-the-wapahani-river/

A few special land reserves were set aside in the treaties for individual Native Americans. One included 320 acres for Samuel Cassman at the confluence of the White River and Buck Creek.

Cassman’s is the earliest recorded land registered in Delaware County on 16 September 1820. It was a prime location in the north half of section 22 in what is now the town of Yorktown, Indiana.

Besides Cassman, there were three other Native American reserves in Mt. Pleasant Township adjoining Cassman’s land: Solomon Tindell, received the southeast quarter of section 15, (160 acres) to the north of Cassman in 1824; Benomi Tindell, received the northwest quarter of section 23, (160 acres), east of Cassman in 1824; and Isaac Wobby, received the south half of section 14, (320 acres).

Wobby claimed to have cleared and planted 10-acres of the land in an 1818 letter but he was tenaciously following the Delaware Indian Agent to Ft. Wayne and then Piqua, Ohio in 1818. Isaac Wobbly died soon after the treaty was signed. There was a court battle over whether his widow, Jane, could inherit and sale his land. His land wasn’t registered in Delaware County until 1832 and was in litigation for many years thereafter. Ultimately, Goldsmith Gilbert purchased all Indian Reserves in Delaware County. He sold Cassman’s reserve to Oliver H. Smith who platted the town of York Town in 1837, naming the town after the Indians from New York.

The 1818 treaty wrongly identifies these individuals as Delaware Indians in full or part. In truth, all but Cassman were Brothertown (Brotherton) Indians.

The New Purchase land was not yet surveyed and could not be legally sold, although that fact deterred few. In May of 1822, the Ft. Wayne land office was created. According to Kemper in A Twentieth Century History of Delaware County Indiana (1908), the land in Delaware County was sold through the Ft. Wayne office with few exceptions.

Many people flooding into the central part of the state were squatters. The pressure was on the tribes in the east to move away from the aggressive trespass of white settlers onto their agreed land reserves. The Native Americans were moved again and again westward.

Who were the Native Americans with land reserves in Mt. Pleasant Township?

While Cassman was said to be half-Delaware, (Cassman’s son refers to his father as a “York” Indian), it is still unknown why he received such a generous grant. The others, the Tindells, father and son, and Wobby, were part of the Brothertown (Brotherton) Indian Nation (Moravian or Christian Munsee)—a Christian tribe formed in 1785 from many related tribes including some Delaware (Lenape), Pequot, Stockbridge-Munsee, Mohican and Oneida.

The Delaware and Miami gave permission to all related tribes in the east to live along the west fork of the White River prior to the treaty but things didn’t quite work out for those invited.

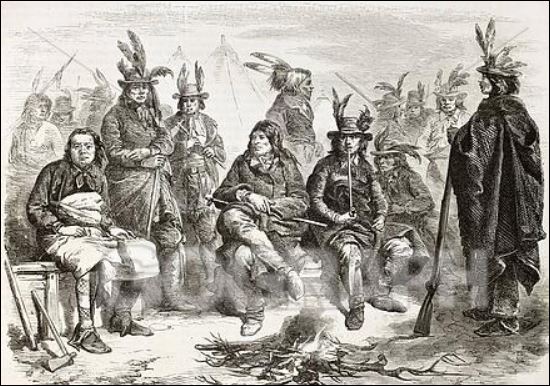

In 1818, while cementing the final details of their move to live along the White River as invited, a delegation from the Brothertown tribes arrived from New York and Massachusetts to Indiana. The Brothertown delegation stopped at villages along the White River, but learning of the treaty, hurried to Ft. Wayne to find Elder Isaac Wobby. Wobby had already gone to observe the negotiations of the Treaty of St. Mary’s, Ohio.

The Brothertown delegation arrived within days of the treaty signing. The Miami and Delaware affirmed the agreement that they had with the Brothertown. Those rights were respected in the treaty. Isaac Wobby’s attendance and tenacity helped ensure the individual land reserves. The reserves were most likely given to sell to finance their move west of the Mississippi. The Stockbridge-Munsee received nothing and had sent no one to St. Mary’s.

None of those receiving a reserve lived on the land except for Cassman and, possibly, Wobby, for a short time. In correspondence, Wobby claimed to have cleared 10-acres on his reserve but wasn’t living on the land at the time of the treaty. There were also reserves for Elizabeth Pet-cha-ka and Jacob Dicks, both Brothertown Indians but these reserves were not in Mt. Pleasant Township.

Rebekah Hackley received a full section of land, plus additional land to compensate for the White River running through her property, 672 acres in all, at “Munsee Town”. The land was “for her inheritance”. The land became known as the Hackley Reserve and encompasses today’s Muncie, Indiana. She was living in Fort Wayne at the time of the treaty.

Although Rebekah Hackley was a granddaughter of Miami Chief Little Turtle (who had numerous grandchildren), her own father, William Wells, had served with the U.S. military after the Revolutionary War. Wells was killed in the 1812 Massacre of Ft. Dearborn (at Chicago). Wells Street, in downtown Chicago, is named for him. Rebekah’s husband, Capt. John “James” Hackley, Jr., negotiated the treaty between the Native Americans and Hackley’s boss, General Anthony Wayne. Hackley was a long-time member of the U.S. military and earlier militias. He likely ensured that he and his wife were treated generously.

Also of note, the Congressional Record of 1820 records a petition from William Conner (THE “Conner” of Conner Prairie Farm) for consideration of a pre-exemption of land in the “Delaware Towns” where he had been living among the Delaware. Conner had married a Delaware woman, Mekinges, daughter of Chief Anderson, and wanted to remain with his wife and rear his six children on lands that he had improved. The petition was tabled.

Unfortunately for Conner, the Delaware Indians had to move. The Delaware had matriarchal linage and Mekinges wanted to move with the tribe west. When the Delaware left Indiana in 1820, Conner rode with his wife and children for a day. He turned around while she continued with the children to Kansas via Missouri, later moving them to Indian Territory in Oklahoma with her tribe. Conner chose to stay in Indiana. He remarried. The six Conner children who were half-Delaware Indian were denied rights to Conner’s estate after Conner’s death.

Under pressure from the United States government in the 1830’s, the remaining Brothertown (Brotherton) in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New York, together with the Stockbridge-Munsee, Moheakunucks (Mohican), and some Oneida, moved to Wisconsin, taking ships through the Great Lakes. They remain settled in Wisconsin. Other tribe members went to Ontario, Canada while others, as we see from above, had already settled in Indiana as early as 1790 had moved to Indian Territory via Missouri and Kansas. Some of the Indiana group went to Wisconsin or Canada but most ended their journey in Oklahoma.

One beautiful day, many years ago, I walked from my mother’s house, down the dirt path, with an eye always looking out for arrowheads. I was walking to see the mighty Sycamore tree along the river. I stopped in my tracks in shock. The tree was lying dead—bulldozed among many trees in the woods—a senseless slaughter evidenced by piles of decaying, unused wood. I crawled on top of that downed, old tree and cried. The feeling of loss was great. The “Keep Out” sign I saw in the corner of my eye only added insult. Soon, the landowner approached asked me to leave. The woods and fields of childhood were now off limits. Déjà vu?

~Julie Musick Hillgrove